“Magic Lantern” or optical lantern is the popular term for 19th and early 20th century slide projectors. The principle of projecting light and the use of crude lenses goes at least as far back as the ancient Greeks. Leonardo da Vinci, in the 16th century, experimented with projection. Magicians and entertainers were probably the first to find practical uses for projection devices as objects to create fantastic illusions in their performances. Using an artificial light source and a combination of lenses, these devices enlarged small transparency images or miniature models and projected them onto a wall or screen. Originally the lanterns were illuminated with oil lamps or candles. In the 19th century newer technologies like carbon arc, acetylene, and incandescent lamps were adapted for use in magic lanterns.

Showmen and lecturers traveled regional circuits presenting images of scientific miracles and geographic wonders never before seen by their enthusiastic audiences. Clergymen often used lantern slides to sow the “wages of sin” to congregations eager for a night of educational education.

Between 1850 and 1940 many technical innovations were made to the lanterns. Projector and lens design improved rapidly, and light sources brightened significantly. Professional lanterns with large glass slides were used until the 1940’s when 35mm slide and film format came into use.

Prior to 1950, most magic lantern slides were hand-painted on glass, or created using a transfer method to reproduce many copies of a single etching or print. In the middle of the 19th century, the development of photographic slides created entirely new uses for the magic lantern. It then became popular for audiences from university lectures to amateur family photo shows.

By the end of the 19th century, the magic lantern was overtaken by the cinematograph, which projected so-called “living pictures.” Magic lanterns just couldn’t compete with these moving pictures. Magic lanterns were soon relegated to being the warm-up act for movies, used to project advertisements before the real shows began. Eventually the apparatus evolved into the automatic photo slide projector, which still remains popular.

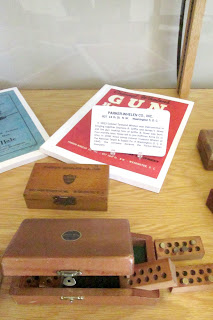

This magic lantern in our collection was donated in 1982 by Don Phillips, whose family owned theaters in Colby for many decades. The lantern was manufactured by Best Device Company in Cleveland, Ohio. It features an enclosed metal light box with an incandescent bulb and primary lens. Another large magnifying lens mounted on rails allows adjusting the lens for focus. Attached to the front of the light box is a wooden slide carrier with space for two 3” x 4” transparencies side by side. One transparency can be projected while the other one is being changed out with another one. The unit is mounted on a green painted 1" x 8" board 37” long. On the front of the board is a hinge and on the other end is a short length of light weight chain. Apparently it was hinge-mounted to the projection room wall and made to drop down out of the way when not in use.

(Click image to enlarge.)

In the last several months, our multi-talented maintenance guy (Larry Dilts) has taken the time to carefully scan the many glass slides and glass negatives in our photo archives. We are grateful to Larry for taking on this tedious task since the slides are very delicate and could be damaged with improper care and handling. Many of the glass slides in our collection show damage caused by abrasion, high humidity or moisture as a result of careless handling and improper storage. Blistering of the emulsion, paint, or dye caused by the high heat of the projector is another source of damage. And the most obvious damage - breakage or chipping. The examples of transparencies from our collection shown below are all on 3" x 4" glass plates and are of the best quality.

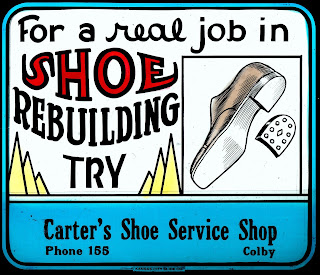

Below are examples of slides used at the Colby theaters for advertising businesses and services.

Theaters also used glass slides provided by movie distributors to promote coming attractions. A blank space was usually left on the transparency for the theater manager to add the show dates.

Our photo collection also contains many glass photographic negatives. Larry also scanned those and converted them to "positive" images which are much easier to view. We are currently in the process of cataloging those into our computer database. I will share some of those in a future post.